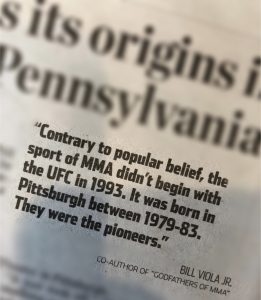

When Did MMA Begin?

The Martial Chronicles: Before Fighting Was Ultimate It Was Super

Would you be a fan of the UFC is it was called Super instead of Ultimate? The forgotten but true story of the first MMA league in the United States. The Martial Chronicles: Before Fighting was Ultimate It was Super

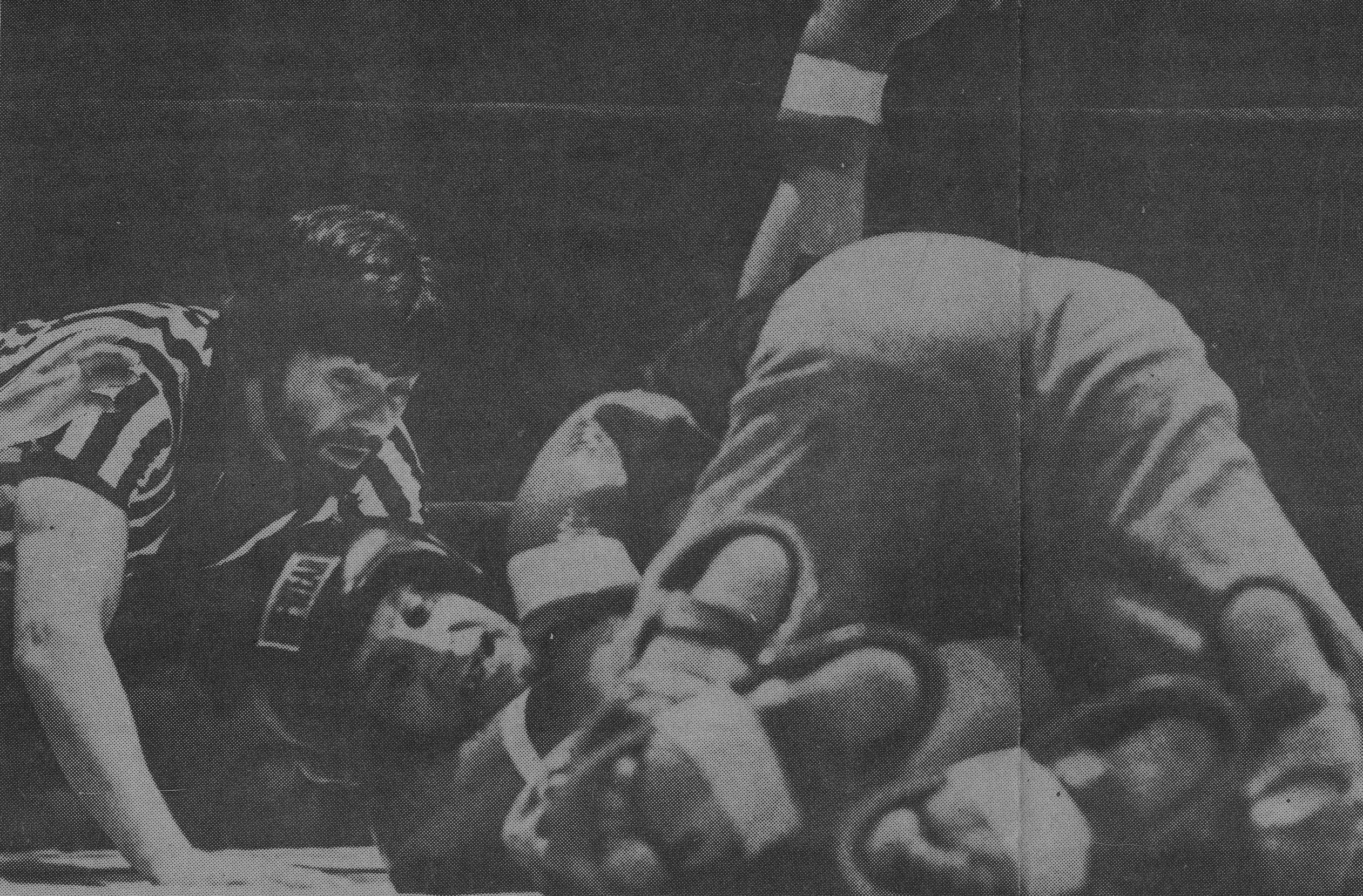

The ballroom of the Holiday Inn in New Kensinton, Pennsylvania was filled to capacity with fight fans who were more than pleased with what was being demonstrated in the ring. Mike Murray, a car salesmen from Vandergrift, Virginia and Dave Jones, a road gang laborer from nearby North Huntingdon, were in the final round of their match, the opening contest of the evening. It had been a back-and-forth affair for most of its three rounds, with a surprising amount of wrestling for two standup fighters: Murray claimed a boxing background while Jones dabbled in karate and kickboxing. As the clock wound down the fighters, along with the spectators, were back on their feet. Jones was now turning it up, unloading a series of vicious kicks and punches that went unanswered from his dazed and damaged opponent. With only seconds remaining in the fight Murray’s corner threw in the towel, saving him from any more punishment. The audience roared in approval.

Scenes such of this can be found all across America on any given day of the week, but what makes this particular contest noteworthy isn’t the results, the participants, or the fight itself, but the date it took place. March 20th, 1980.

One evening in late 1979 Bill Viola Sr. and Frank Caliguri were having dinner together at a Denny’s Restaurant when they came up with an idea that not only changed their lives but came very close to changing the history of mixed martial arts. The two men had become friends and business partners thanks to their shared background and interest in martial arts. Both held black belts in Shotokan karate as well as owned and taught at their own schools: Caliguri’s Academy of Martial Arts and Viola’s School of Shotokan Karate (which also included boxing and kickboxing in the curriculum). For the past few years they had been working together promoting kickboxing events around Western Pennsylvania, and it was this business they were discussing over hamburgers and coca-cola when the conversation turned towards the common misconceptions the layman had about martial arts and what they were really interested in seeing.

One evening in late 1979 Bill Viola Sr. and Frank Caliguri were having dinner together at a Denny’s Restaurant when they came up with an idea that not only changed their lives but came very close to changing the history of mixed martial arts. The two men had become friends and business partners thanks to their shared background and interest in martial arts. Both held black belts in Shotokan karate as well as owned and taught at their own schools: Caliguri’s Academy of Martial Arts and Viola’s School of Shotokan Karate (which also included boxing and kickboxing in the curriculum). For the past few years they had been working together promoting kickboxing events around Western Pennsylvania, and it was this business they were discussing over hamburgers and coca-cola when the conversation turned towards the common misconceptions the layman had about martial arts and what they were really interested in seeing.

To the patrons at the bars they visited to promote their shows there was heard the common refrains. That karate or wrestling was a fraud. That the fighters they were promoting were “bums” whom their detractor could beat up. What was better: Karate, boxing, or wrestling? Who would win if Mohammed Ali fought Bruce Lee? How about either against Bruno Sanmartino? Could I do better than those guys?

The two were suddenly struck by an idea. What if we let the average guy try his hand at fighting? To prove that he was as tough or tougher than any of these so-called experts? And what if we let them use whatever style they wanted? Wrestling, boxing, karate, whatever. Finally, people could start to settle the age-old debates of what worked best in a fight.

The two knew they had come up with something special and shortly thereafter they co-founded CV Productions (C or Caliguri and V for Viola) with which to promote their new venture. With his experience and familiarity with karate, kickboxing, boxing, Judo and Japanese jujutsu Viola was chosen to write up the rules, which he quickly did from his home, coming up with an eleven-page book covering almost every aspect of the newly created sport. Fights would take place over three 2-minute rounds during which almost all techniques or styles of martial arts were permitted, including ground fighting and judo/jujutsu or pro wrestling submission holds. Rules were also instituted to cover weight classes, open fingered safety gloves, headgear, ring side doctors, back stage physicians, professional referees, judges scoring, fighter contracts and the banning of certain attacks such as eye gouging and groin strikes.

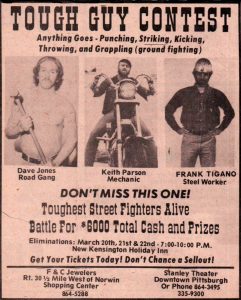

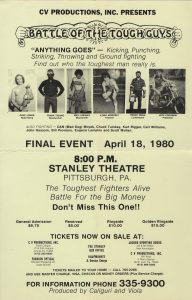

With the debut of what they were calling a “Tough Man Contest” booked for March of 1980 the two men began making the rounds to local bars and gyms. They were in search of the “toughest street fighters alive” to compete in what was being billed as “Anything Goes – striking, throwing, grappling, punching, kicking, ground fighting, and more”. All participants were also to be amateurs. Experienced boxers or martial artists above green belt were banned from taking part.

Early on it came to their attention that a Michigan promoter by the name of Art Dore was already hosting amateur boxing events at this time under the title “Toughman Contests.” Viola and Caliguri immediately changed the events name to that of the “Tough Guy Contest” in order to avoid any confusion. (Unfortunately, it didn’t work as well as planned and this confusion over names would eventually come back to haunt them.)

Word of the event spread and the two were surprised to find themselves being flooded with queries from interested parties. Where before they would get 100 phone calls asking questions about an upcoming kickboxing show, within the first week alone they got 1500 calls concerning Toughguys. As Viola recalled years later, “They were from Yonkers, NY. They were from Michigan, Florida. The word got out and it just went totally out of control. We had to actually hire secretaries. (Before that) we were nothing. We were just mom-and-pop karate schools.”

Besides adding secretaries to their staff, Viola also left his job teaching science at Allegheny High School in order to promote and organize the event full time. Such was his confidence in its appeal.

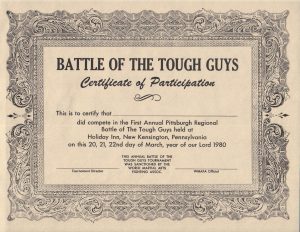

The first “Tough Guy Contest” show was a 3-day event, taking place on the 20, 21, and 22 of March and consisting of two 8-man tournaments to crown the “Toughest Guy” in the heavyweight and lightweight divisions. The winners would also receive $1000 and the chance to participate in the as yet unscheduled state-wide Tough Guys championships.

The show, which had the tag-line “The Real Thing in the Ring”, was kicked off by the previously mentioned Jones/Murray contes. The event, as described by the News Dispatch, sounded very familiar to long time fans of MMA.

The show, which had the tag-line “The Real Thing in the Ring”, was kicked off by the previously mentioned Jones/Murray contes. The event, as described by the News Dispatch, sounded very familiar to long time fans of MMA.

The contestants “all wore contact karate gear and were permitted to employ any style fighting within prescribed limits. The results were spectacular. Some punched, some kicked, some grappled, but all gave their best effort.” A five-foot-six-inch, two hundred forty pound truck driver wrestled his way to victory over a much taller, two-hundred-pound mechanic that tried to box him. Two fighters named “Mad Dog” and “Crazy Jack” engaged in a wild, slugfest. Another fighter came out in a trench coat beneath which he had concealed an array of weapons. He then proceeded to slide various chains, billy clubs, and a tire iron across the ring to his opponent, telling him “you’ll need this… you’ll need this…” The ring girls, Margie, Mary Kay, Kathy, and Gloria, became the objects of adulation amongst the fans. And, after the fights, “once the bell rang, the men would shake hands, pat each other on the back and embrace each other.”

“I’ve never seen anything like it.” said one spectator. “I’ll never go to another wrestling match if I can got one of these instead.”

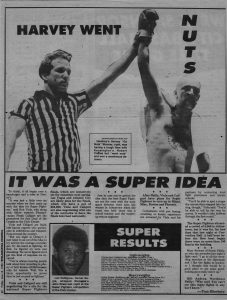

The event sold out all three consecutive nights. Tough Guys, or Super Fights as they soon rechristened it, was a hit.

“It was the birth of what many are calling a new sport” announced the News-Dispatch. “A sport that blends elements of boxing, wrestling, and brawling.”

Viola and Caliguri immediately began planning not only the next event, but many more to follow. The idea now was to hold a series of regional tournaments, eliminators, before concluding with a Tough Guys finals.

Super Fighter shows followed in quick succession: “the Battle of the Brawlers” was held on April 18th at the Stanley Theater in Pittsburgh, followed by an even more successful “Battle of the Tough Guys” on May 2nd and 3rd which drew crowds of 6,000 both nights to the Cambria Country War Memorial Arena in Johnston, Pennsylvania.

Shortly thereafter KDKA Television’s Evening Magazine did an in-depth report on the “Battle of the Brawlers”, in which they labeled it “organized, legalized, street fighting.”

The show, which received extensive coverage in the Philadelphia papers, wasn’t as successful as their previous events, drawing only a little more than a thousand per night, but it provided a couple of very valuable answers. One, it proved that they could draw outside of their Pittsburgh home base. Viola and Caliguri always had faith that it would be embraced by the public, citing the “realism factor” as its chief appeal. (Although one spectator at the Convention Center gave a simpler reason, “you can’t see this many fights in any bar I know.”) They had been proven correct again, and were now confident that Super Fighters could be taken anywhere and find an audience. It was time to take it to the next level.

- Frank Caliguri Bill Viola Sr.

- MMA

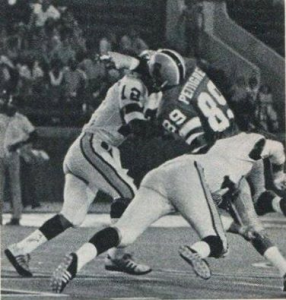

The other lesson learned that evening was provided by Len Pettigrew, a former NFL defensive end with the Philadelphia Eagles, who took part in the heavyweight tournament and ripped through the competition. Although technically an amateur with no martial arts training to speak of, he was too fast, too strong, and too athletic for his opponents. It was now obvious that it would be impossible to keep the tournament strictly for amateurs. Not only had past contestants expressed interest in fighting again, but there was also a desire to see the best in other sports – boxing, wrestling, judo, kickboxing – try their hands in no holds barred competition. The only solution would be to create a professional division.

Big thing were now in the works. Caliguri and Viola founded the World Martial Arts Fighting Association (WMAFC) to sanction competitors and rank fighters for what was to be a professional division of Super Fighters. They also drafted documents to franchise the league and began negotiating television contracts. Preparations were made for a national Super Fighters tour in 1981. in which they anticipated fifty such elimination events around the country, with Phoenix, Louisville, Rochester, Boston, and Philadelphia already being scheduled. The finales would be held in either Atlantic City or Las Vegas, with the championship match being broadcast live on network television and the winner awarded $100,000. Attorney James Irwin was retained to negotiate the television deal. Big-time (relatively speaking) sponsorship was now coming in.

Big thing were now in the works. Caliguri and Viola founded the World Martial Arts Fighting Association (WMAFC) to sanction competitors and rank fighters for what was to be a professional division of Super Fighters. They also drafted documents to franchise the league and began negotiating television contracts. Preparations were made for a national Super Fighters tour in 1981. in which they anticipated fifty such elimination events around the country, with Phoenix, Louisville, Rochester, Boston, and Philadelphia already being scheduled. The finales would be held in either Atlantic City or Las Vegas, with the championship match being broadcast live on network television and the winner awarded $100,000. Attorney James Irwin was retained to negotiate the television deal. Big-time (relatively speaking) sponsorship was now coming in.

“Battle of the Tough Guys is a legitimate sport and not just a passing fad…” was the opinion given by Jim Isler of the News-Dispatch following their October event. It seemed as if nothing could stop Super Fighters from becoming the major sport that Caliguri and Viola had been certain it was destined to be.

“Battle of the Tough Guys is a legitimate sport and not just a passing fad…” was the opinion given by Jim Isler of the News-Dispatch following their October event. It seemed as if nothing could stop Super Fighters from becoming the major sport that Caliguri and Viola had been certain it was destined to be.

On November 6, the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission ordered CV Productions to cancel that evening’s show in Greensburg. If they did not the PSAC threatened to have the police shut it down for them. Caliguri and Viola chose to ignore this command, confident that the Commission had no jurisdiction over their competitions. The shows went on as planned that weekend but now they had attracted the the attention of state officials. Not wishing to antagonize the commission any further they refrained from more shows until the matter could be sorted out. In the meantime they focused on their big plans for the next year.

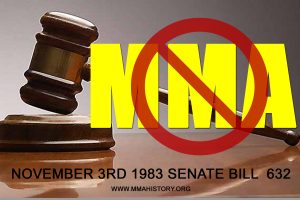

Disaster struck in March of 1981, when 23-year-old Ronald Miller was killed participating in a “Toughman” boxing competition in Johnstown. The name had come back to haunt them. Even though the event had no connection whatsoever to Super Fighters or CV Productions, Inc. most were unable to distinguish this fact and newspaper even mistakenly identified his death as having taken place in a “Tough Guy” competition. Miller’s death and the outrage that followed led to the Pennsylvania Legislature launching an investigation into all fighting events. After careful consideration and considerable legal consultation,Viola and Caliguri put a hold on promoting events while they waited for the storm to pass. But there would be no lull. In 1983, the Pennsylvania State Senate passed a bill that specifically called for:

PROHIBITING TOUGH GUY CONTESTS OR BATTLE OF THE BRAWLERS CONTESTS

It would go on to define this to mean any competition in which individuals “attempt to knock out their opponent by employing boxing, wrestling, martial arts tactics or any combination thereof and by using techniques including, but not limited to, punches, kicks, and choking.”

It would go on to define this to mean any competition in which individuals “attempt to knock out their opponent by employing boxing, wrestling, martial arts tactics or any combination thereof and by using techniques including, but not limited to, punches, kicks, and choking.”

After less than a year in activity and over 10 events held across the state of Pennsylvania, Super Fighters was no more. It would be over a decade before another promotion would try and bring an “Anything Goes” fighting league to the United States. They would succeed, giving birth to a new sport, while Bill Viola and Frank Caliguri and their Super Fighters would be forgotten having been too far ahead of their time.