SCRAPPERS – The Start of Mixed Martial Arts

“Iron is full of impurities that weaken it; through forging, it becomes steel and is transformed into a razor-sharp sword. Human beings develop in the same fashion.”

-Morihei Ueshiba

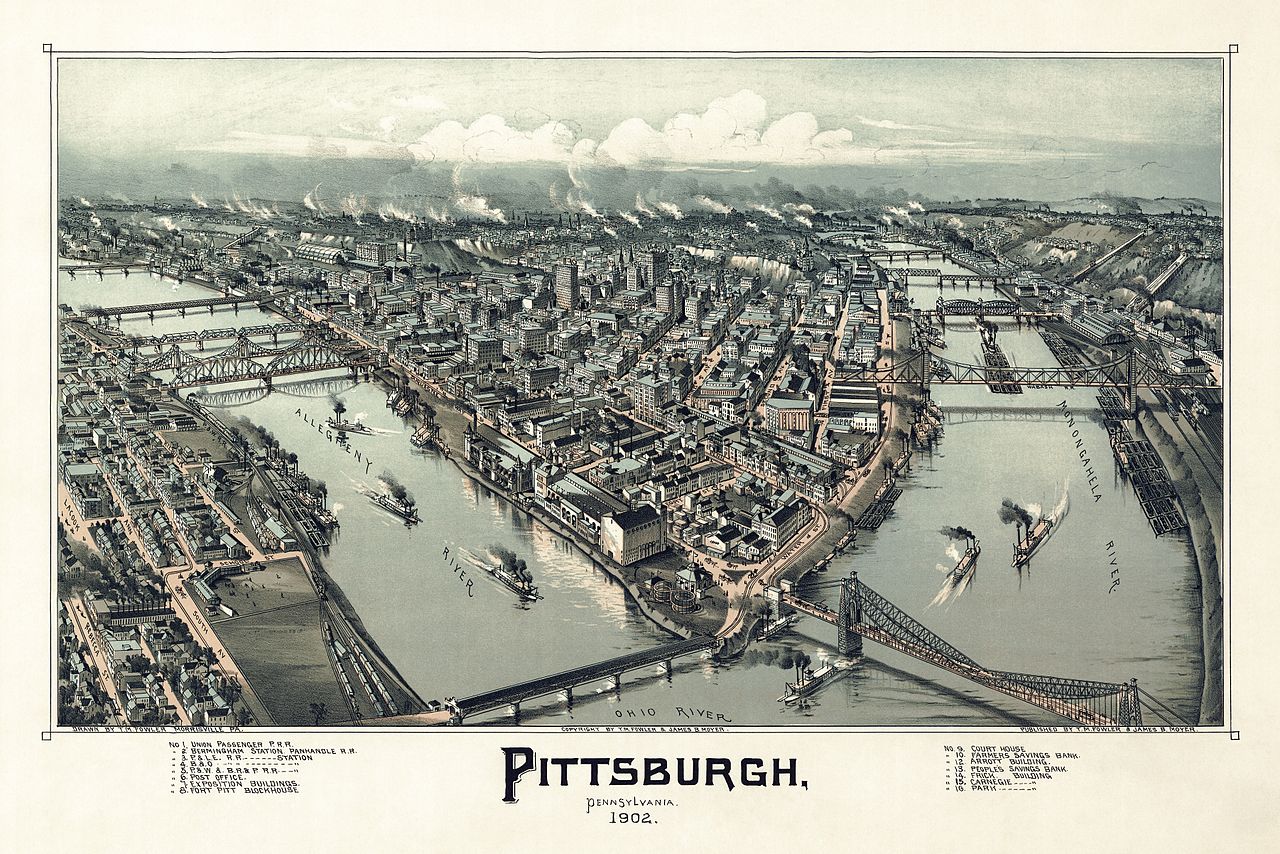

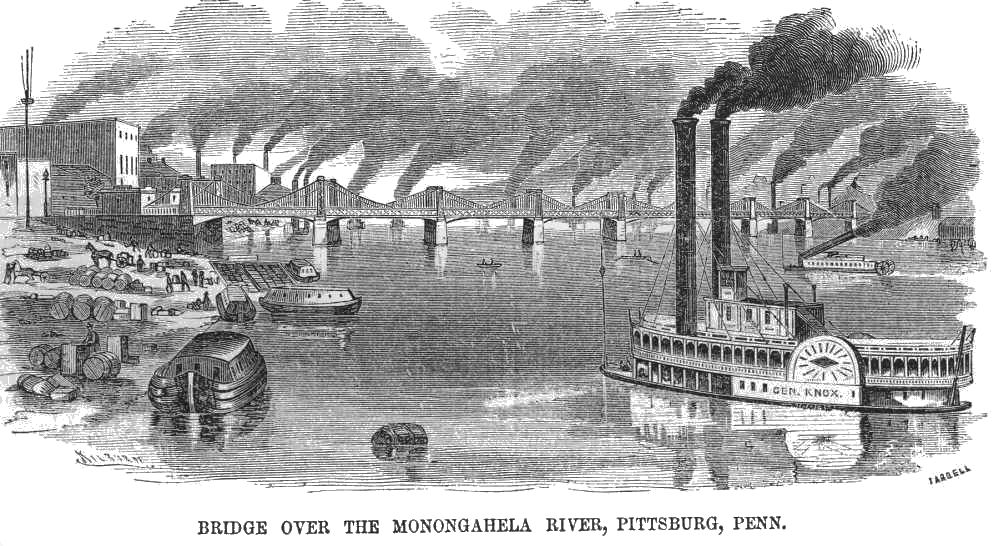

Many factors contributed to the start of mixed martial arts in Western Pennsylvania. The mills, the mines, and the coke works attracted immigrant labor from any number of countries, the classic melting pot which became a crucible for the sinewy toughness among these men. That melting pot threw together people of all cultures, and with them all facets of life unique to those cultures, including combat. These circumstances cultivated a personality peculiar to Western Pennsylvania, and characteristic of its blue-collar workers.

Immigrants in Western Pennsylvania lived a hardscrabble life. As successive waves came from different countries at the turn of the 20th century, each new group was subjected to bigotry and abuse from established society. America began as a country in which almost everyone came from somewhere else, and having fought to establish themselves, each group jealously protected its respective niches and the lives they’d developed against newcomers. America was the land of opportunity, but opportunity must be accessed and utilized; nothing came freely or easily to the new workers.

Not knowing the new land’s language, immigrants were exploited at every turn, and often bullied and harassed by people who had been in the same circumstance a few years before. Their struggle reached beyond the established citizens. Company exploitation of the immigrant workers was endemic. Brutal labor and deadly working conditions toughened the miners in ways few exercise regimens could. In the patch towns of the region, workers lived in ranks of duplex “company” houses, and the streets were intentionally segregated by ethnic origin: one street of Italians, one street of Poles, one street of Russians, one street of Turks, one street of Slovaks. On each street, the native language was spoken, and the companies did little to encourage literacy in English. The children from one street weren’t allowed to play with those from the others. Wholesale distrust, lack of communication, and illiteracy were cultivated by the companies to prevent the organization of labor unions, and they largely succeeded for a generation.

Not knowing the new land’s language, immigrants were exploited at every turn, and often bullied and harassed by people who had been in the same circumstance a few years before. Their struggle reached beyond the established citizens. Company exploitation of the immigrant workers was endemic. Brutal labor and deadly working conditions toughened the miners in ways few exercise regimens could. In the patch towns of the region, workers lived in ranks of duplex “company” houses, and the streets were intentionally segregated by ethnic origin: one street of Italians, one street of Poles, one street of Russians, one street of Turks, one street of Slovaks. On each street, the native language was spoken, and the companies did little to encourage literacy in English. The children from one street weren’t allowed to play with those from the others. Wholesale distrust, lack of communication, and illiteracy were cultivated by the companies to prevent the organization of labor unions, and they largely succeeded for a generation.

The following generation shared a common language, but inherited the biases and prejudices of their forebears, and each ethnic group harbored an antagonism toward those who competed for jobs and sustenance during a new tribulation, the Great Depression. Beyond the economic collapse of America, the western Pennsylvanians endured an even greater hardship, the closing of the mines. Fred Adams: My father recalls that one Friday afternoon the miners’ shift ended, and the company simply announced that the mine was closed, effective immediately. Frick, Carnegie, Thompson and others extracted as much coal from the region as could be profitably dug, then unceremoniously rode away, taking the wealth with them and leaving an entire region lying like an emptied purse on the hollow ground.

Survival of the Depression was a tough pursuit for most Western Pennsylvanians. My grandmother told the story of a neighbor woman complaining about the smoke from the coke ovens spoiling the clean sheets she’d hung out to dry. A passing peddler overheard her complaint and wagged his finger at her saying in the eloquence of broken English, “Lady, lady! Schmoke-business. No schmoke-no business.” The closing of the mines meant the closing of the coke works and many of the dependent mills. As ecologist Barry Commoner says, “Everything is connected to everything.” The double blow of economic collapse and mine closures delivered a setback from which Western Pennsylvania has never completely recovered. Effectively stranded in an economic dead zone by lack of income and lack of mobility, displaced workers had to struggle to keep themselves and their families alive. They had little materially, but they had their pride, and any challenge to it was answered with a fist.

One way to earn money in those days of mass unemployment was in the prize-fighting ring, and many men pursued that course. Win or lose, there was a purse, and many fed their families by climbing in the ring and taking a pounding from more experienced fighters. Others did the pounding themselves and walked away with the bigger money. Another way was to fight in back alleys in bare-knuckle pick up fights while men bet on the winner, as celebrated in films like Hard Times or Every Which Way But Loose, a practice that has persisted to our generation. Every town had its champion brawler. No polished technique, no gym-tuned bodies, just brute strength and determination. These were men built by years of swinging a pick or a sledgehammer and schooled by countless fights in taverns, street corners, and on picket lines.

The perpetual conflict between company and worker is the stuff of legend, and Western Pennsylvania is rich with the history of union-management combat. In the 1860s, Irish immigrants brought the Molly Maguires with them to the Pennsylvania coal fields, waging war with abusive companies. The companies fought back with their own security forces and Pinkerton detectives. My great-grandfather was a company policeman who rode the coal trains to prevent sabotage during labor disputes. He had to lie prone in an open coal gondola and cover himself with coal to prevent being shot by union snipers. Both sides played for keeps. The companies hired strikebreakers who waded into picket lines with truncheons and nightsticks. The miners fought back with pick handles and their fists and ultimately prevailed.

The fights were not confined to the coal fields, either. The Homestead Strike of 1892 resulted in a battle between workers and 300 imported Pinkerton thugs that left seven workers and three Pinkertons dead and dozens injured. The Lattimer Massacre of 1897 left 19 unarmed striking Polish, Slovak, Lithuanian, and German immigrant miners dead at the hands of a sheriff’s posse. 49 more were injured and all were shot in the back by the deputies. But such incidents galvanized the workers and strengthened their cause. What they had fought to gain, they would fight to keep, with their bare hands if necessary.

When World War I loomed large, the military draft inducted a multitude of the newly minted Americans into the armed forces. It is difficult to convince the descendants of those fin de siecle immigrants that their forebears were treated equally by the draft and the military in the assignments to the front lines. The disproportionately high per capita of combat casualty experienced by immigrant groups from Pennsylvania was evident, as opposed to that of the blue bloods of New England or the Southern gentry. They were the perfect candidates for the trenches of Europe: they had strong backs, they took orders well, and in many cases they were fluent in the languages of the theatre in which they fought. Those who returned came back with a stake in America’s present and its future and had a patriotic reverence for their new country. What they had earned through their sweat and blood would not be surrendered, nor could it be taken easily by the rich and the powerful.

World War II was a critical benchmark in the acceptance of immigrants, especially of Italian Americans. Their wholehearted support of the war and their unusually high ratio of service in the military legitimized them in American eyes. The war also transformed many “Little Italy” neighborhoods, as men and women left for military service or to work in war industries. Upon their return, many newly affluent Italian Americans left for suburban locations and fresh opportunities, further eroding the institutions and contadino culture that once thrived in their old ethnic enclaves.

Class distinctions and ethnic boundaries eroded further with each generation, but Western Pennsylvanians never forgot their struggle for integration into American society, and that core of hard-won pride remains just below the surface of their congeniality. To this day, an open hand can still close into a fist at the first sign of disrespect.

It is this fighter’s personality that paved the road for what would become the origin of a new sport in America in 1979: Mixed Martial Arts. It began at the hands of two enterprising martial arts promoters and the fists and feet of scores of willing and eager Pennsylvania “tough guys.” read more