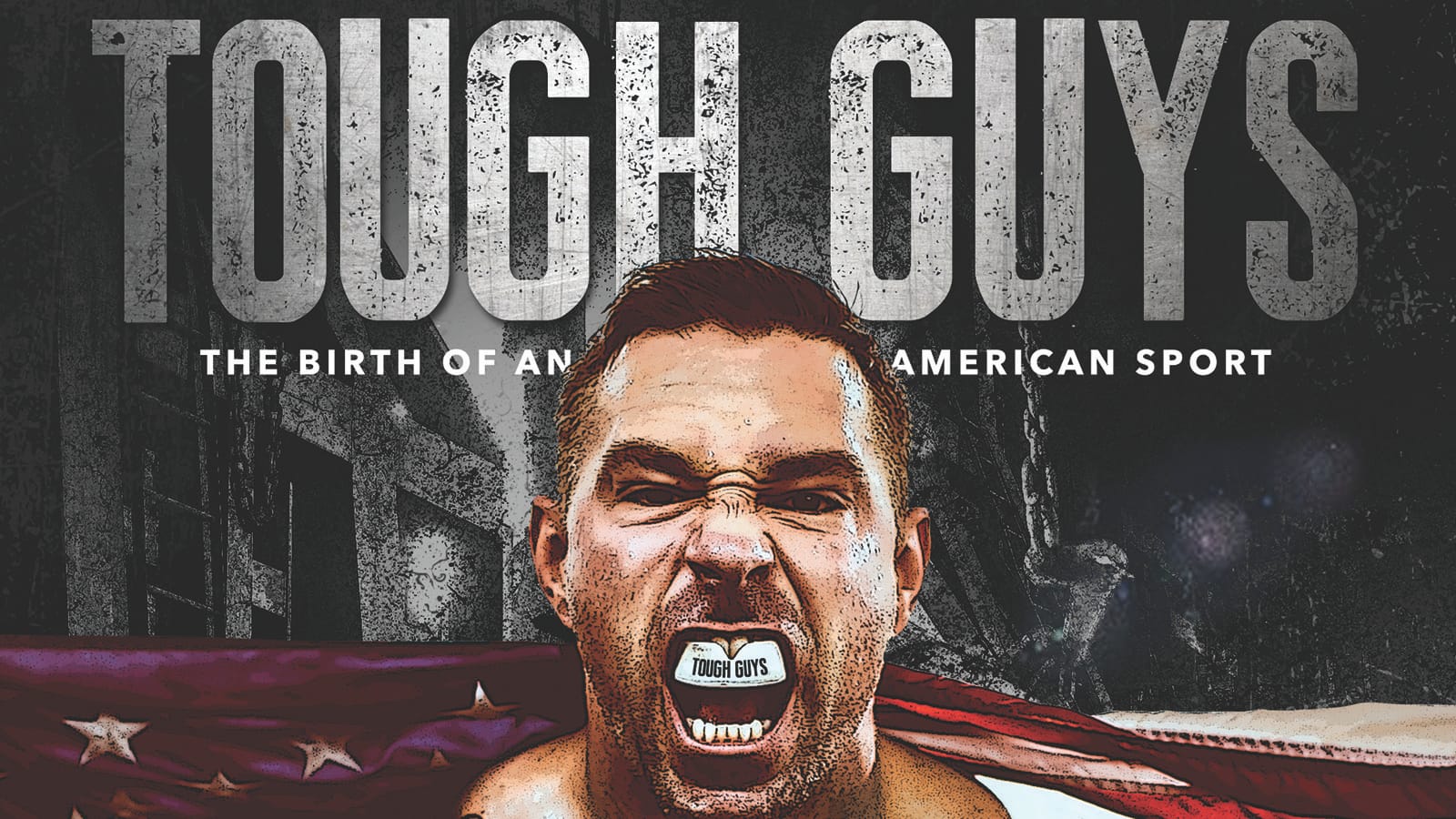

Pittsburgh MMA

From Pittsburgh roots, MMA, UFC have grown to staggering heights’

- Fist MMA League

- Super Fights

- First regulated sport

- MMA

- First Superfighters

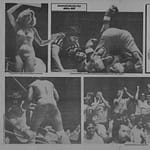

- First MMA fight in Philly

‘This is something that happened in less than a decade. It’s kind of unprecedented.’

February 19, 2016 12:31 PM

In a sports culture that increasingly draws attention to the dangers of head injuries and in which the average person couldn’t name boxing’s heavyweight champion, the Ultimate Fighting Championship is defying the odds.

The mixed martial arts promotion is filling arenas everywhere and persuading fans to hand over gobs of money for pay-per-view events. Its most famous fighter, Ronda Rousey, is a superstar followed by more than 2 million people on Twitter.

On Sunday, fans will pack into Consol Energy Center to see the violent and sometimes bloody fights in person. UFC Fight Night 83 is the organization’s second visit to Pittsburgh.

But until recently, MMA existed on the fringe, developing passionate fans who passed around VHS tapes of fights and discussed the sport over online chat rooms, while the UFC battled to remain legal in the face of government opposition.

“It went from being this super-niche, almost carnival-type sport, where if you weren’t really hardcore into it you probably didn’t even know it existed, to a sport that was on national TV and was available widely,” said Jonathan Snowden, combat sports reporter for the website Bleacher Report. “This is something that happened in less than a decade. It’s kind of unprecedented.”

The UFC bills itself as the fastest-growing sports organization in the world. It came into being only 23 years ago — more than a decade after martial artists in Pittsburgh started the first regulated MMA organization.

“It’s one of the first sports that was really developed on the Internet,” said Matt Leyshock, who runs Pinnacle Fighting Championships, an MMA promotion in Pittsburgh. “That’s how it all stayed cohesively together while it was illegal.”

The glory of MMA

While the UFC is not the only MMA organization, it is by far the largest and has contracts with the world’s top fighters, said John S. Nash, who writes for the MMA website Bloody Elbow.

“People don’t think of MMA as the sport,” he said. “They think of UFC as the sport.”

Battles between lesser-known fighters open UFC events, and the main card acts as the headliner, similar to boxing. But unlike its pugilistic predecessor, UFC offers monetary bonuses for the best bouts, incentivizing all combatants to go hard.

“The most exciting thing of the night could be in the first fight with two people you’ve never heard of,” Mr. Snowden said. “That’s the glory of mixed martial arts.”

The fights, which take place in an octagon-shaped cage, are violent and visceral, matching the entertainment value of scripted professional wrestling with the unscripted reality and athleticism of all combat sports.

“They literally close the cage door and lock it,” Mr. Snowden said. “You can’t even imagine the experience.”

Before it became a worldwide brand with events on five continents, the UFC was a fringe organization battling to remain legal in the U.S. In the late 1990s, Arizona Sen. John McCain urged governors to outlaw the sport, which he called “human cockfighting,” and pressured television companies to pull it from pay-per-view. Thirty-six states barred the sport, although New York is the only state where it remains illegal.

“America was against this sport,” Mr. Snowden said. “Politicians, cable companies wanted to see it dead, and they were very close to making that happen.”

But the organization fought back. The UFC’s current management purchased the promotion in 2001, when it brought in $4.6 million in revenue. The new ownership returned the UFC to pay-per-view and also brought it onto cable television. The reality television show “The Ultimate Fighter” catapulted the UFC brand, bringing MMA to millions of homes.

Last year, it raked in more than $600 million in revenue, Mr. Nash said.

Combined fighting

While UFC has become culturally synonymous with MMA, the sport predates the organization by more than a decade.

The sport, which has origins in Brazil and even ancient Greece, took root in Pittsburgh, which was home of the first regulated MMA promotion in 1979.

CV Productions, the MMA company by Pittsburgh martial artists Frank Caliguri and Bill Viola, is the forgotten forerunner of the sport. They have gotten more recognition in recent years, as Mr. Viola’s son, also named Bill, chronicled Pittsburgh’s deep MMA history for the book “Godfathers of MMA,” and the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum began exhibiting the local ties.

“I want Pittsburgh to be proud of this,” the younger Viola said recently. “We don’t just have all these Super Bowl titles. We started one of the most popular sports in the world right now.”

Like UFC, CV Productions’ so-called Tough Guy Contests allowed athletes to draw on myriad techniques from martial arts — or just pure muscles.

“You had no clue what these guys were showing up with, so you were going purely on their reputation, purely on their ego, purely on what people were telling you,” Mr. Viola Jr. said.

The sport — called “combined fighting,” before the term “mixed martial arts” was invented — tapped into Pittsburgh’s blue collar heritage. With the region reeling from a weak economy, CV Productions offered hefty prizes for winners and the promise of becoming the next “Rocky.” The first bout, at the Holiday Inn in New Kensington, matched a laborer against a car salesman. (The laborer won.)

“But the sport ended almost as quickly as it had begun,” Anne Madarasz, director of the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum, wrote in the journal Western Pennsylvania History. “Pressure from the boxing commission and wrestling federation … combined with a death in a similarly titled but unrelated ‘Tough Man’ boxing event in Johnstown, led to the banning of all tough guy and brawlers contests.”

In 1983, Pennsylvania became the first state to ban the sport, although it was legalized again in 2009. The UFC debuted in Pittsburgh two years later.

“This had all the makings of where we are today,” Bill Viola Jr. said. “Frank and my dad just didn’t have enough money to fight it.”

Straight out of the movies

Still, Pittsburgh has strong ties to the sport it incubated.

Hidden inside the garage of an Oakland apartment building, the Conn-Greb Boxing Club is so underground that many of the building’s residents do not know it’s there. The gym comes straight out of the movies: the faded oriental rugs, the low ceilings, the posters and photographs papering its walls.

It is here that Chris Dempsey studies boxing, one of the four combat sports in his toolkit. As a UFC fighter, Mr. Dempsey, 28, also uses techniques from wrestling, kickboxing and Brazilian jiu-jitsu. The Ambridge resident spends about 40 hours each week training at gyms across the Pittsburgh area and as far away as Texas.

The Pittsburgh area has produced a handful of UFC fighters, including Mr. Dempsey, Adam Milstead and Cody Garbrandt, who trains in California and will compete at Consol on Sunday.

“I think MMA in Pittsburgh is flying under the radar a little bit,” said Mr. Dempsey, a former wrestler at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown, who will compete in next weekend’s UFC Fight Night in London. “There’s no better area for wrestling in the country other than Western Pennsylvania, so I really think it’s an untapped market that sooner or later is going to become huge.”